How the real estate industry is protecting cities from climate change

Better building standards are among efforts to help the built environment withstand the changing climate

Wildfires, hurricanes and flooding are among the extreme weather events putting the real estate industry under pressure to ensure the built environment can cope with the effects of climate change.

One solution gaining traction as a way to protect billions of dollars’ worth of properties: better design and efficiency standards that make sure buildings are able to withstand an increasing range of climate conditions and hazards.

In recent years, many global frameworks and standards have been introduced around low emissions, net-zero carbon and green buildings. But until recently few provided guidance or measured resilience to climate-related impacts.

“Green and net-zero buildings are so important from a climate mitigation perspective, but we also need to consider resilience,” says Lucy McCracken, an associate in JLL’s global sustainability team. “Building codes and standards can be an effective way of minimizing the effects of extreme weather on buildings and communities.”

For instance, codes can promote the use of wind or heat-resistant construction, or better storm-water management.

Voluntary standards are being developed to guide resilient design. Take RELi, a first-of-its-kind rating system and certification focused on climate resilience – such planning and design, emergency preparedness, and social cohesion.

“Green building standards mitigate a property’s impact on the environment, but resilience is about ensuring the built environment can withstand outside effects,” McCracken says.

Designing for the decades ahead

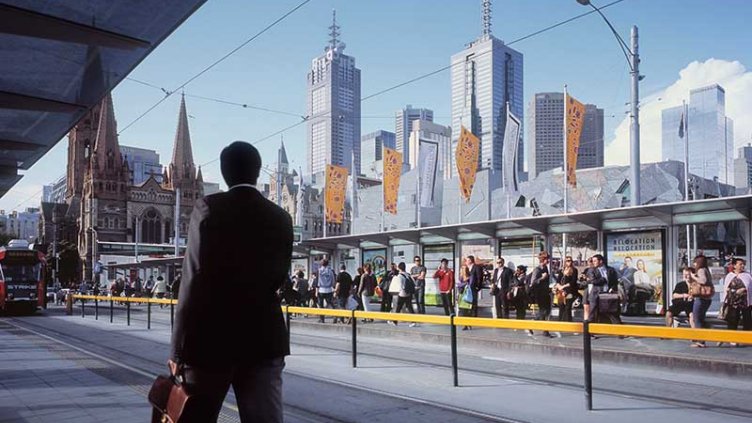

Cities in the U.S., Canada and Australia are leading the way in implementing other new standards.

Boston has a climate advisory group as well as policies requiring climate resilience measures be implemented in new developments, and has established the Climate Ready Boston initiative to ensure major projects are planned for future climate scenarios.

Toronto and Melbourne have produced checklists and guidelines covering areas such as extreme temperature events, back-up power generation for critical services, flood mitigation and occupier preparedness to improve climate resilience planning in new developments or major redevelopments.

“Local authorities in these markets are putting a stake in the ground and saying resilience is an area of importance going forward,” says Matthew McAuley, director, global research, JLL.

The risk of ignoring resilience standards

Resilience is rising up the real estate agenda because investors increasingly want to understand how to guard against future risks and financial losses.

For example, more resilient buildings often require less ongoing expenditure, and can be better equipped to return to normal operations following short-term disruptions.

“A certain amount of climate change is now baked in and the industry needs to take that into account on construction or developments that are expected to last decades,” McAuley says.

The risks are clear. Assets that aren’t climate-proofed risk obsolescence and lack of interest from future investors. There is further regulatory risk as mandatory standards rise, as well as extra costs associated with retrofitting properties to meet new measures.

“There is a push on the regulatory front and investors are asking whether this trend is going to get stronger so they can be prepared,” says McAuley.

Taking transparency to new heights

The imperative to tackle climate change has presented the property industry with new transparency pressures in recent years.

Climate action plans have helped countries like Belgium to join the top improvers in JLL’s Global Transparency Index, which includes new benchmarks measuring resilience initiatives in anticipation of this growing trend.

But while sustainability becomes a mainstream issue for governments, real estate investors and corporate occupiers, mandatory measures are still limited.

McAuley expects resilience standards to quickly move up the agenda as investors phase out non-certified buildings from their portfolios and look for a minimum climate-proofing standard in new acquisitions. Others could retrofit properties to meet resilience criteria.

Investors who fail to take future climate impacts seriously could be left behind, McAuley says.

“To withstand the test of time, assets need to meet sustainability targets and resiliency measures will become an important aspect of that,” he says.