How many tourists is too many?

Local authorities and the hospitality sector are taking action to implement more sustainable tourism models for popular destinations

The hospitality industry, benefiting from surging tourism worldwide, is scrambling to keep up with demand while remaining aware of the potential pitfalls from the deluge of tourists.

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, tourism and travel spending grew 3.9 percent in 2018, compared to global economic growth of 3.2 percent. The sector generated US$8.8 trillion in revenue in 2018 and accounted for 10.4 percent of global economic activity.

“Budget airlines, new technology promoting destinations, and a greater disposable income among a rising global middle class in countries like China and India have led to a travel boom,” says Pitinut Pupatwibul, senior vice president, JLL Hotels and Hospitality APAC.

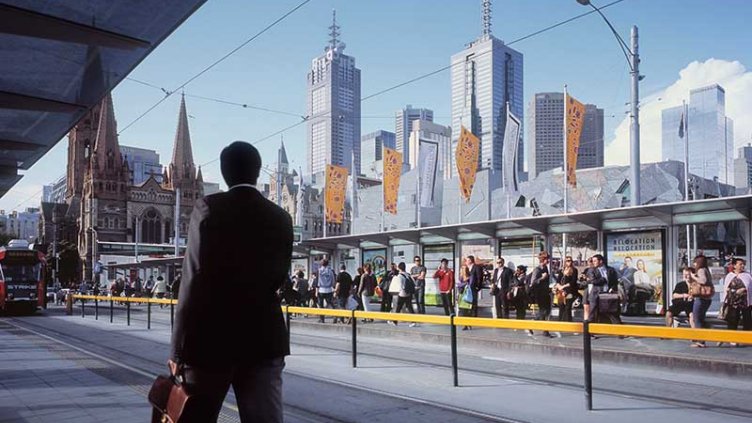

Hotel construction has responded. In Australia, nearly 300 hotels are in the works to cope with greater numbers of tourists. In China, the hotel pipeline is at an all-time high.

“More tourists means more rooms are needed. And it’s not just in the cities,” says Pupatwibul. “Travelers are exploring beyond the usual spots thanks to a mix of social media and government campaigns promoting them.”

“When left unchecked by authorities, it causes overtourism,” she says.

Curbing tourist numbers

The phenomenon of overtourism has led cities and rural locales around South East Asia, Japan and Europe struggling with the deluge of travellers. From Dubronik and Venice in Europe to Phuket and Kyoto in Asia, beautiful destinations are caught between the resultant economic spoils and the social costs.

While hordes of travelers keep the hotels busy, the longer-term fallout from overtourism can hurt business.

The island of Boracay in the Philippines was closed to tourists fox six months last year, as authorities said they sought to clean up the damage caused by tourism. The shutdown cost the island US$1 billion in lost tourism revenue. Hotels that failed to meet standards were not allowed to operate. As of December, new guidelines limit the daily number of tourists arriving to 6,400.

In Iceland, new hotel construction was banned in downtown Reykjavik last April, following similar steps taken by Barcelona, which passed an accommodation law in 2017 to stop hotels from being built in the city centre.

“New rules will be put in place to combat overtourism. I foresee more of such laws as well as authorities taking a tougher stand on hotels to ensure compliance to minimize environmental damage,” says Pupatwibul.

Globally, more destinations are starting to implement measures to control tourism. Bali is among the latest to announce it will be charging a US$10 levy on foreign tourists to fund efforts to preserve the environment. But the gold standard of “high value–low impact” tourism can be seen in Bhutan. Visitors to the Himalayan kingdom need to book with a government accredited travel agency and pay US$250 a night to cover basic accommodation, a local guide, food and transportation.

The way forward

Some hotels are banding together to combat the effects of overtourism. Phuket’s Hotel Association and its members have rallied together to reduce plastic use, pledging to phase out plastic water bottles and straws by this year.

Pupatwibul suggests hotels can demonstrate more responsibility by screening tour operators and agents they partner with, curating external services provided to ensure standards and safety and educate guests about travelling more sustainably.

“As it’s impossible to stop the flow of tourists, there is more urgency than ever in managing tourist numbers and planning ahead,” she says. “All stakeholders – hotels, travel operators and authorities – can work together to create more sustainable travel.”